Vilnius,

Lithuania. Uzupis Jewish cemetery. Photo: Samuel D. Gruber 2015.

Vilnius,

Lithuania. Uzupis Jewish cemetery before destruction.

Vilnius,

Lithuania. Uzupis Jewish cemetery before destruction.

Vilnius,

Lithuania. Uzupis Jewish cemetery. The 2004 monument. Photo: Samuel D. Gruber 2015.

Vilnius,

Lithuania. Uzupis Jewish cemetery. Volunteers clearing vegetation, 2015. Photo courtesy Vilnius Municipality.

Lithuania: Uzupis Jewish Cemetery in Vilnius No Longer Forgotten

by Samuel D. Gruber

In 2000, when I first visited the enormous "New" Jewish cemetery on Olandų street in the Uzupis area of Vilnius (usually referred to as the Uzupis Cemetery and formerly as the Zaretcha Street cemetery), the site was, despite its huge size, a well guarded secret. There were no signs, no markers, and no open paths. Some clearing of the site had just begun. The hillside nearest the road has been cleared and the remains of some graves were visible. Tramping through the woods with representatives of the Vilnius Jewish Community we were able to identify, at the crest of the hill, the bases of some earlier (boundary?) walls, and that was all. But the dominant appearance of the site was of wooded hillsides, with a road (Dalildžių) cut right through it, and a large not-Jewish funerary hall built right off this road. At the time, the Jewish Community of Vilnius had plans for a monument and hope for fencing and clearing the cemetery so that its original form and purpose would be recognized, and the thousands of still-intact graves would be respected and protected. Now, fifteen years later, there has been significant movement toward these goals.

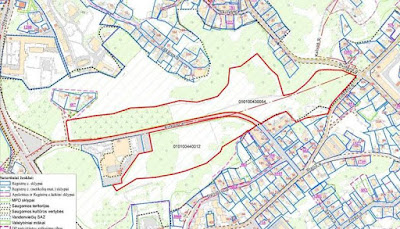

Vilnius, Lithuania. Uzupis Jewish cemetery. Olandu street is on the left you can see how the "new" road cuts through the cemetery (view below). The red lines indicates the cemetery limit - I cannot say for sure that this corresponds exactly the historic boundary. Map from "Special Plan of Pavilniai Regional Park," courtesy Vilnius Municipality

Vilnius, Lithuania. Uzupis Jewish cemetery. Dalildžių Road cuts through the heart of the cemetery site from Olandu street. The 2004 monument is on the left. Photo: Samuel D. Gruber 2015.

Under the German rule, Nazi and Lithuanian collaborators marched tens of thousands of Vilna Jews and others out of the city to the Ponary Forest (Paneriai), where they executed and buried approximately 100,000 people, of whom 70,000 are believed to have been Jews. Later other Jews were forced to exhume and burn them, in a failed attempt to hide the crimes. The Ponary site is now a memorial park. Beginning in 1991 new monuments were erected and a small museum is also located here, too. An annual commemoration is held at Paneriai every September 23rd, and this year plans are being made to renovate and in someways re-define the memorial site (I'll write about this when more details are available).

Under Soviet rule, from the 1950s through the 1970s, tens of thousands of Jewish gravestones were ripped from the graves they marked at the historic "Old" and "New" Jewish cemeteries in the city. Even in the 1990s, when Lithuania began to grapple fitfully with its history under German and Russian rule, few people were ready to confront the scale of devastation that those occupations brought first to Vilnius's large living Jewish community and then to its dead. The history of these cemeteries has been recognized in fits and starts, but their future remains contentious and unresolved.

Already in 1993, during the period when the Jewish Community led an effort to gain recognition and protection for Jewish cemeteries and mass grave sites throughout the country, the Uzupis Jewish Cemetery was listed into the Cultural Heritage Register, though cultural heritage officials showed little understanding of the historical and religious significance of the site. The large Uzupis Cemetery, had been totally desecrated in the 1960s, when, during the Soviet period, all the stones were pulled, a large road (Dalildžių) cut through the middle of the hillside site and a new (non-Jewish) funeral hall erected on part of the site. In many official documents and even today, the place is referred to as the "former Jewish cemetery," when in fact it is a Jewish cemetery plain and simple. Is artistic value has been compromised, but even though the matzevot (gravestones) have been removed, Uzupis remains the burial place of generations of Vilna Jews.

The cemetery was founded in 1830 by the Vilnius Jewish Community funeral brotherhood after burials ceased at the cemetery in Šnipiškės near the Neris River. The new burial place included a large mortuary in the center and tree-lined avenues and other planned pathways. The more than 70,000 people who were buried at this site included prominent poets, publishers, scientists, bankers, educators, and religious leaders. Burials at the Uzupis cemetery ceased in 1948. A lengthy description can be found in Israel Cohen's classic history and description of the city written in the 1930s and published in 1943 (quoted here).

Beginning in 1964, Communist authorities removed the gravestones and used many as building material at other locations, with some becoming stairs on Taurakalnis (Tauras Hill). Only a small number of human remains were reburied elsewhere. Surviving Jews in Vilnius had the option of relocating family graves to the new Jewish cemetery. These and graves of venerated rabbis, some of which like the Vilna Gaon had already been moved from Snipiskes in the 1950s, were transferred to new graves. Most remains - of tens of thousands of Jews - were left behind.

Vilnius, Lithuania. Suderves Road Jewish Cemetery. Participants in European Jewish Cemeteries conference visit the Ohel of the Vilna Gaon and other sages, whose remains were transferred from Snipiskes and then Uzupis Cemetery. Photo: Samuel D. Gruber 2015

Vilnius,

Lithuania. Suderves Road Jewish Cemetery. Grave of Vilna Gaon transferred from Snipiskes and then Uzupis Cemetery. Photo:

Samuel D. Gruber 2015

A recent exhibition at the Vilnius Jewish Community Center, when the conference on Jewish Cemeteries in Europe was held, presented photos taken by Rimantas Dichavicius just before the destruction of the cemetery. These beautiful images, which were shown at the Vilnius City Hall in 2004, show the vast and formerly beautiful extent of the Uzupis Cemetery (it would be good to publish these photos and other documentation about the cemetery).

Photographer Rimantas Dichavicius at Vilnius Jewish Community Center. Photo: Samuel D. Gruber 2015

Vilnius, Lithuania. Exhibit of photos of Uzupis Jewish Cemetery by Rimantas Dichavicius at Vilnius Jewish Community Center.

After Lithuania’s independence was restored in 1991, the Lithuanian Jewish Community and the Lithuanian Culture Fund arranged for the dismantling of the Tauras Hill steps and some other structures built using the gravestones (though more structures with gravestones have since been identified). Until recently, there were no markers anywhere indicating that this is a Jewish cemetery. In 2000, members of the Jewish Museum staff began clearing part of the hillside closest to the main road and revealed the stumps of several dozen gravestones. Further back in the cemetery are traces of the original masonry boundary wall.

Some of this work was probably linked to the negotiation and signing of a bi-lateral cultural heritage agreement between the governments of Lithuania and the United States in 2002, which led to the recognition of Jewish and other religious and ethnic minority heritage sites. The Jewish Community had already envisioned a monument at the site where no historical or commemorative markers existed. A project was already developed (in the 1990s?), designed by architect Jaunutis Makariūnas, to be built of Jewish gravestones that had been removed from the cemetery in the 1970s and reused in the steps of the Tauras Hill. These comprise just a tiny percentage of Uzupis gravestones reused in building throughout Vilnius, and the retrieval of hundreds - if not thousands - of known matzevah fragments incorporated in to steps and walls - remains a pressing task (I wrote about this back in 2011, and it is still a pressing problem, so more on this later). Only faint inscriptions can be read on some of the stones in the monument, as these were cut and refinished into uniform blocks as part of their re-purposing.

After 2002, members of the U.S. Commission worked with the Jewish Community and the city of Vilnius to raise money for the monument which was essentially complete in 2004, though the multi-lingual plaques were not affixed until 2006 (?), due to lengthy discussions about their content.

[n.b. I was tangentially involved in this project, and was engaged to provide the Commission with a brief history of the site and help in drafting historical information to include on the monument. On a recent visit to the Uzupis Cemetery with many participants in the Jewish Cemeteries in Europe Conference this inscription engendered a lively discussion - and therefore I will address it and the broader subject of the "art" and "folly" of inscription writing in separate blog. Apropos the original matzevah inscriptions, presentations at the conference demonstrated that new technologies and processes, that might now allow these nearly-invisible inscriptions to be read.]

For some in the Jewish community the inauguration of the monument marked the beginning of a long-overdue recognition of the history and sanctity of the place. The cemetery was now listed in some guidebooks, and the occasional Jewish heritage tour stops there to pay respects. But it appears that for many in the government and for the U.S. Commission, the completion of the monument marked the end of responsibility - since little more was done to study, clear and maintain Uzupis for almost a decade.

Vilnius, Uzupis Jewish cemetery. Clearing of tress and brush has revealed a small number on gravestones or their bases still in situ. Photo: Samuel D. Gruber 2015.

The good news is that in 2012 the Municipality of Vilnius adopted a "Special Plan of Pavilniai Regional Park," of which the cemetery site is the primary component. The plan was approved and as I understand it, it recognizes the historic boundary of the cemetery and includes plans for conservation. In 2012-2013 the site was surveyed and in 2014 it was fenced. In 2015 intensive cleaning of the Cemetery site began that included cutting trees, revealing the old paths, and uncovering the bases of some gravestones. No heavy equipment is being brought in in order not to disturb the graves themselves, so cutting and hauling is done by hand and many volunteer groups are participating. The work is organized by the Vilnius Jewish community, the State Department for Heritage Preservation and the Vilnius Municipality.

My understanding of this project, as it was briefly presented at the conference, is that in the end this will be a public park for walking, and that no permanent entertainment, recreational of service facilities will be built on the site. Information kiosks or signs are planned, however, along the boundary of the cemetery, and these will include relevant historical and religious information about the place, the community and noteworthy individuals buried there.

Vilnius,

Uzupis Jewish cemetery. Monument. Photo: Samuel

D. Gruber 2015

Vilnius,

Uzupis Jewish cemetery. Thinned woods. Photo: Samuel

D. Gruber 2015

Vilnius,

Uzupis Jewish cemetery. Cleared hillside. Photo: Samuel

D. Gruber 2015

1 comment:

thank you for this history

Post a Comment