Dankmar Adler (1844-1900). Photo: http://www.auditoriumtheatre.org/media/Image/landmark/photos/aud-photo4.jpg

by Samuel D. Gruber

Chicago, Il. Isaiah Temple. Dankmar Adler, architect (1898). Now Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church. Photo: Samuel Gruber, 2008

Happy Birthday Dankmar Adler! (born July 3, 1844)

Today is the 170th anniversary of the birth of noted Jewish-American architect and engineer Dankmar Adler, who gained famed in Chicago in the last decades of the 19th century. Adler was born in Stadtlengsfeld, Germany, and came to America in 1854 with his father, Rabbi Liebman Adler, stepmother and siblings. The family settled in Detroit, and later moved to Chicago. Dankmar's grandfather had also been a rabbi or teacher.

Adler is celebrated in Chicago as one of those who helped reshape the city after the great fire of 1871. He is remembered as a great engineer; a pioneer of public halls with excellent acoustics, as one of the creators of the Chicago or skyscraper style, and for his partnership with Louis Sullivan that produced important and innovative buildings such as the Wainwright Building in St. Louis, Missouri (1890-91), the Chicago Stock Exchange Building (with Sullivan, 1894, demolished), the Guaranty Building in Buffalo, NY (1895-96). Adler's Chicago Central Music Hall (1878-80, demolished), Auditorium Building (with Sullivan, 1889) and Kehilath Anshe Ma'ariv Synagogue (with Sullivan,1890-91), were celebrated for their acoustical engineering.

Chicago, IL. Auditorium Building, Adler & Sullivan, architects (1889). Photo: Samuel D. Gruber, 2004

Buffalo, NY. The Guaranty Building, Adler & Sullivan, architect (1895-96). Photo: Samuel D. Gruber, 2013.

Adler is not, however, usually remembered as an architect of synagogues, or even as a Jewish architect. Paul Sprague's 1982 entry in the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architecture (Vol 1, 34-35) only treats Adler's work with Sullivan, and makes no mention of his religion or his synagogues. Thirty years later Adler's Wikipedia biography, for example, designates him as "a celebrated German-born American architect." This may have been enough during the Civil War and the years following when Adler received his training. Actually, at the time it was probably advantageous to be designated German rather than Jew. But Adler never separated himself from his religion, as did immigrant Jewish New York architect Leopold Eidlitz. I can't say that Adler brought anything specifically Jewish to his architecture - though his interest in acoustics and interior space may have begun as a boy having to sit through so many services. But he certainly brought architecture and design to synagogues.

Chicago, Il. Sinai Congregation (Temple Sinai). Dankmar Adler et al (1875, 1891-2, demolished)

Today, however, Adler's Judaism is of some interest, because he belonged to a very small fraternity of Jewish architects practicing in 19th-century America. The best account of Adler's early life and career pre-Sullivan (1880) is by his granddaughter Joan W. Saltzstein, prepared with Charles E. Gregersen and included in Gergersen's monograph Dankmar Adler: His Theatres and Auditoriums (Ohio Univ. Press, 1990). Saltzstein got information direct from an autobiographical manuscript drafted by Adler, now in the Newberry Library, and from Adler's account we know he was deeply rooted in his Jewish community. His father Liebman Adler was rabbi of Chicago's first synagogue, the Kehilath Anshe Mayriv (K.A.M.) Temple, from 1861-1883, and his father-in-law Abraham Kohn was an early settler in Chicago (1844), prominent businessman, and founding member of K.A.M. Temple. Kohn also was friends with local politician Abraham Lincoln and in 1861 presented Lincoln a painting of an American Flag with Hebrew lettering on it [see Inventory of the Dankmar Adler Papers, 1857-1984].

In Detroit, Liebman Adler had been hired as the second rabbi to serve the still new Beth El Society (today's Temple Beth El), which by 1856 was already adopting reforms, which soon led to a congregational split in 1861, the same year that Rabbi Adler chose to move to Chicago to lead Kehilath Anshe Maarav (KAM) an older congregation but one that was also moving toward Reform. Both Beth El and KAM would go on to be among the first members of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Young Dankmar, however, was thoroughly Americanized, though German would have been a common language in mid-century Detroit. He attended public schools in Detroit and Ann Arbor, but because he didn't pass the entrance exams to the University of Michigan his father found him employment with architect John Schaefer who introduced Dankmar to some basics of architectural drawing. In 1861, in Chicago, he entered the office of German-born architect August Bauer, where he may begun to learn some engineering. But in July 1862, Adler enlisted in the First Regiment of the Illinois Light Artillery, and remained in the army, fighting in Kentucky, Tennessee and Georgia, until discharged at the end of the war in 1865. During the last nine months of his enlistment he was attached to the Topographical Engineer's Office of the Military Division of Tennessee as a draftsman. This is where his real training began, and where he changed from immigrant to insider. He wrote "I made as good use of my time and was well equipped for my life's work as if my studies had been pursued at home."

After the war Adler joined the firm of Ozia D. Kinney, where he soon became foreman, supervising the erection of religious and institutional buildings throughout the Midwest. When Kinney died in 1869, Adler joined in partnership with Kinney's son to form Kinney & Adler, which continued work until 1871, when Adler went to work with more senior architect Edward Burling. This was the year of Chicago's Great Fire - and for the rest of the decade Burling and Adler could hardly keep up with the work. It was during this period that Adler developed what would be his working method - where he would plan the buildings' form and structure, but would leave the "dressing" to others. In 1880 he went out on his own, but hired the young Louis Sullivan as his assistant and soon-to-be partner. For the next 15 years the pair designed scores of buildings including several functional and aesthetic masterpieces, especially the Auditorium Building which really established their fame. The partnership ended amicably in 1895. The economy was bad, their style had fallen from fashion, and work was slow.

Chicago, Illinois. Zion Temple. Adler & Sullivan, architects (1885). Original design with towers. This harks back to more famous two-towered Moorish designs of the 1860s. Photo from Gregersen, Dankmar Adler, 1990, fig. 41

Chicago, Illinois. Zion Temple. Adler & Sullivan, architects (1885). Too bad we don't know the colors here. Photo from Gregersen, Dankmar Adler, 1990, fig. 43

Chicago, Illinois. Zion Temple. Adler & Sullivan, architects (1885, demolished 1950). Facade as built without towers. Gregerson writes (p. 62): "Although the original design of the front with its twin onion-domed towers would have made the building somewhat monumental, the omission of these features in the completed building gave it a stumpy appearance that Sullivan's crude Moorish-inspired details only accentuated." Photo from Gregersen, Dankmar Adler, 1990, fig. 42

In the 1875-76, when still with Burling, Adler designed Sinai Temple, after a limited competition against four other architectural firms. Adler's Jewish credentials may have helped win the commission, which he executed with the help of John H. Edelmann, possibly assisted by Sullivan. The most remarkable feature was the tall square dome atop a central facade tower, flanked by lower towers with similar domes. Adler & Sullivan were subsequently hired in 1891 to substantially lengthen the building, which led to a complete interior renovation. The facade dome is a fairly common element on synagogues in the 1890s (such as Brunner's Beth El in NY), but this may be one of the earliest examples (I'll explore this in a future blogpost).

Chicago, Il. Sinai Congregation. Dankmar Adler et al (1875, 1891-2). From postcard.

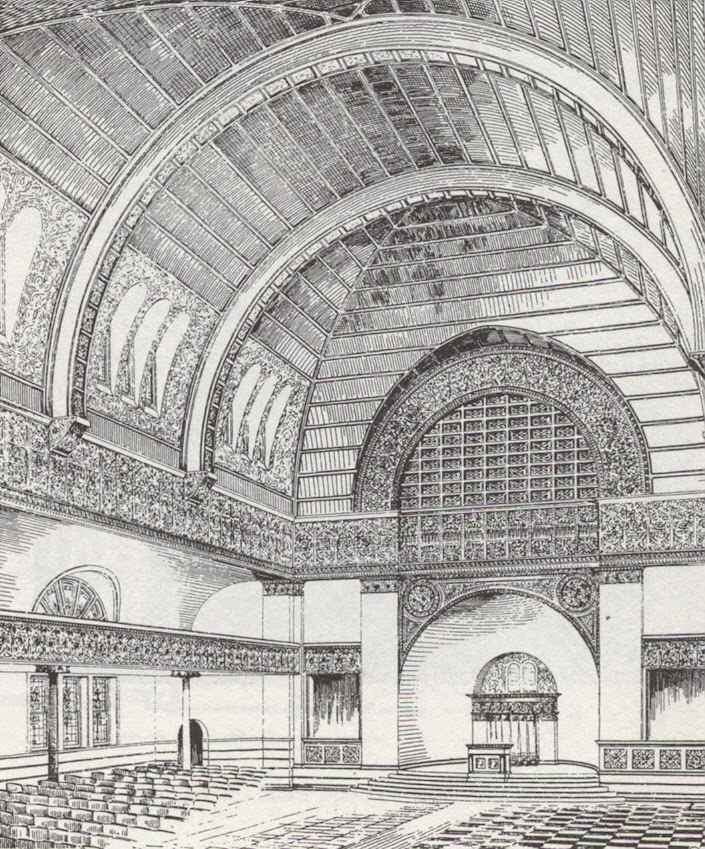

Chicago, Il. Sinai Congregation. Adler & Sullivan (1891-2 remodel). View to bimah.

Adler & Sullivan employed a robust and integrated use of the Moorish style in their Zion Temple of 1884-85, though their original design was not built in full - the two ornamental towers were left off - unfortunately truncating the design. Later, their buildings tended toward variations of the Romanesque style. This is best seen in what is their most admired synagogue, the new K.A.M Temple built in 1890-91, which later served the famous Pilgrim Baptist Church until the interior was destroyed be a devastating fire in 2007.

Chicago, Il. K.A.M. Temple. Adler & Sullivan (1890-91). Historic photo.

Chicago, Il. K.A.M. Temple. Adler & Sullivan (1890-91). Historic photo.

Chicago, Il. K.A.M. Temple. Adler & Sullivan (1890-91). Interior.

Chicago, Il. K.A.M. Temple. Adler & Sullivan (1890-91). After fire. Photo: Samuel D. Gruber (2008).

In the late 1890s, the same years that New York synagogue architect Arnold W. Brunner (1857-1925) was developing his new Jewish classicism, Adler also changed the outward appearance of his buildings in Chicago - perhaps for personal reason, but more likely to keep up with the post-Columbian Exposition times. His Temple Isaiah of 1897-98, the last building he finished, was designed in a Palladian style much more in keeping with the new American Renaissance taste than anything he had previously designed. Today, the building is well maintained as the Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church (and I thank the church deacons for facilitating my visit back in May, 2008). Although the synagogue/church has an Ionic portico surmounted by a large arch on one side, and one window wall articulated with a large triple arch, the overall effect is still subdued and almost utilitarian – much like a music hall or train station. It does not stand out as a civic monument. The overall effect is similar to that of some contemporary churches, which in the 1890 began increasingly to transform their Romanesque detailing to Renaissance forms. Temple Isaiah, however, has no bell tower.

Chicago, Il. Isaiah Temple. Dankmar Adler, architect (1898). Now Ebeeezer Missionary Baptist Church. Photo: Samuel Gruber, 2008

Chicago, Il. Isaiah Temple. Dankmar Adler, architect (1898). Now Ebeeezer Missionary Baptist Church. Photo: Samuel Gruber, 2008

Adler died in 1900, soon after the completion of Temple Isaiah, but its influence lingered. In the next five years, several examples of Renaissance style synagogues recalled Temple Isaiah in form and some details, but these buildings are all surmounted by central domes. Classicism in different forms continued in Chicago Reform synagogues for more than a decade and then was picked up again by Orthodox and Conservative congregations in the 1920s. One of the finest contributions was by the young Jewish architect Alfred Alschuler (1876-1940) who, after graduating from the Armour Institute of Technology (now IIT), went to work for Adler, probably just as Temple Isaiah was completed. Alschuler later designed many important Chicago buildings, including synagogues, but his classical style Sinai Temple of 1909 (now Mount Pisgah Missionary Baptist Church), not far from Temple Isaiah, remains one of his best.

For further reading see:

Charles E. Gregerson, Dankmar

Adler: His Theatres and Auditoriums, with a

biography of Dankmar Adler prepared in collaboration with Joan W.

Saltzstein. (Athens, Ohio: Swallow Press/Ohio University Press, 1990).

For photos and brief histories of various Chicago congregations, see Lauren Weingarden Rader, "Synagogue Architecture in Illinois," Faith & Form: Synagogue Architecture in Illinois. An Exhibition Organized by the Spertus Museum (Chicago: Spertus College Press, 1976); and also George Lane, Chicago Churches and Synagogues: An Architectural Pilgrimage (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1981).

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment