|

| Elias Hadiis at KKJ. Photo: Mariela Lombard. |

|

| Richard Zabot at the Walnut Street Shul, photo: Samuel Gruber 2018. |

Historic Synagogues Have Lost Two Good Friends: Ilias Hadiis and Richard Zabot

May Their Memories by a Blessing

by Samuel D. Gruber

Last month we learned of the deaths of two men who played a big role in keeping Jewish life and Jewish history alive in two historic American immigrant-founded synagogues.

In New York, if you’ve visited Kahila Kedosha Janina on Broome Street either for a service, or on a Sunday when the museum is open, it is likely you met Ilias Hadjis, a longtime congregant of Kehila Kedosha Janina, and original member of our Board of Trustees. Ilias died in mid-February, He was a cherished docent of the museum, telling his own story, and the story of the Jews of Greece. Ilias was born in 1937 and lived, as a young child, through the Occupation. His family was from Volos and Chalkis. He was the son of Mayer Hadjis and Emilia Cohen; he is survived by his wife, Cookie, his daughter, Emily, his grandson, Michael, his brother, Ephraim and sister, Nina Tapia. Ilias's big open smile and his welcoming ways were one of the many reasons that KKJ has survived a turbulent time and emerged as a vibrant religious and community space. He will be missed.

|

| Elias Hadiis at Purim service, KKJ. Photo: 2019. |

|

| Elias Hadiis at Purim service, KKJ. Photo: 2019. |

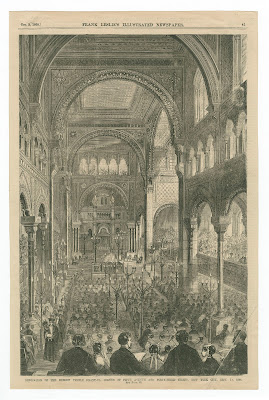

In Chelsea, Massachusetts – just across the Mystic River from Boston – the same could be said for Richard Zabot, who died on February 9th. Richard was one of the mainstays of the history Congregation Agudath Shalom, perhaps better known as the Walnut Street Shul, which has in recent years emerged as an important history and culture center as well as continuing Orthodox congregation. Richard devoted a lot of his time and energy into sustaining the Walnut Street Shul, and collecting history and artifacts of the once-expansive Chelsea Jewish community, Of more than 20 immigrant-founded congregation that filled this small urban enclave in the early 20th century, only the Walnut Street Shul continues in the 21st.

|

| Richard Zabot at the Walnut Street Shul, photo: Samuel Gruber 2018 |

|

| Richard Zabot at the Walnut Street Shul, photo: Samuel Gruber 2018 |

Richard was a follower of this blog, but my lack of proof-reading really annoyed him. During the pandemic he graciously proof-read many of my more recent posts. My last communication with Richard, however, was some months ago about his idea to create a mural at the Walnut Street Shul - perhaps a birds-eye view or a map - showing where all the Chelsea shuls once were, with painted images of the different synagogues popping out. He wrote: “What I am envisioning is a wall mural depicting all the shuls we have photographs of, the Kosher butchers and bakeries, the Jewish-owned businesses on Broadway. The mural would be on a wall in the larger of the 2 sanctuaries downstairs. The purpose would be to increase the exhibit space of what is becoming a museum of early twentieth-century Jewish Chelsea.”

Maybe we can still do something like this in his memory.

Donations in the memory of both these men can be sent to their respective synagogues.